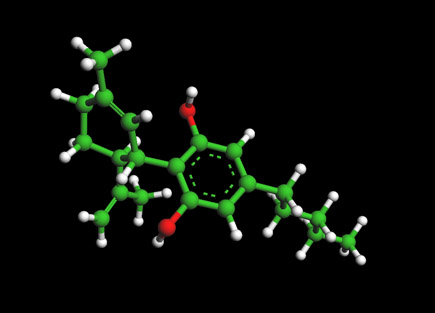

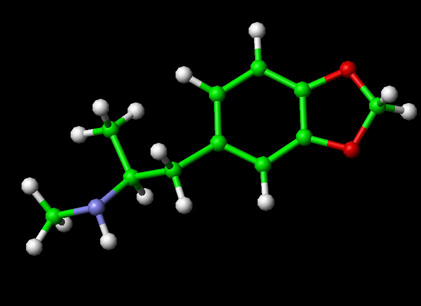

MDMA Molecule - Methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine

Ball and Stick Model for MDMA Molecule - methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine

To View the MDMA Molecule in 3D --->>in 3D with Jsmol

MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-methamphetamine, chemical formula of C11H15NO2 and molecular mass of 193.25 g/mol is most commonly known today by the street name ecstasy (often abbreviated to E, X, or XTC), is a semisynthetic empathogen-entactogen of the phenethylamine family. MDMA was first made in 1912.[14] It was used to improve psychotherapy beginning in the 1970s and became popular as a street drug in the 1980s. It has greater stimulant effects and fewer visual effects than other common "trip" producing drugs. It is considered mainly a recreational drug, though is often used as an entheogen and as a tool to supplement various practices for transcendence, including in meditation, psychonautics, and psychedelic psychotherapy, whether self-administered or not. MDMA is illegal in most countries, and its possession, manufacture or sale may result in criminal prosecution.History

MDMA is often rumored to have been first synthesized by the famous German chemist Fritz Haber in 1891; however, this is incorrect.[2] The patent for MDMA "referred to as methylsafrylamine"which is not under dispute, was originally filed on December 24, 1912 by the German pharmaceutical company Merck, after being first synthesised for them by German chemist Anton Kallisch at Darmstadt earlier that year.[3][4] The patent was granted in 1914; Köllisch died in 1916 unaware of the impact his synthesis would have. This study was discontinued due to the high costs of the chemical synthesis. Interest was revived in the compound as a possible human stimulant by Wolfgang Fruhstorfer in 1959, although it is unclear if tests were actually performed on humans. The synthesis of the compound first appeared in 1960.[5] The U.S. Army did, however, carry out lethal dose studies of MDMA and several other compounds on animals in the mid-1950s. It was given the name EA-1475, with the EA standing for either (accounts vary) "Experimental Agent" or "Edgewood Arsenal."[6] The results of these studies were not declassified until 1969. MDMA appeared sporadically as a street drug in the late 1960s (when it was known as the "love drug"). MDMA began to be used therapeutically in the late-1970s after the chemist Alexander Shulgin tried it himself, in 1977,[7] then introduced it to psychotherapist Leo Zeff. As Zeff and others spread word about MDMA, it developed a reputation for enhancing communication, reducing psychological defenses, and increasing capacity for introspection. However, no formal measures of these putative effects were made and blinded or placebo-controlled trials were not conducted. A small number of therapists "including George Greer, Joseph Downing, and Philip Wolfsonâ€"used it in their practices until it was made illegal. Due to the wording of the existing Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, MDMA was automatically classified as a Class A drug in 1977 in the UK. In early 1980s USA, MDMA rose to prominence in certain trendy nightclubs in the Dallas area, then in gay dance clubs.[8] From there use spread to rave clubs, and then to mainstream society. The street name of "ecstasy" was coined in California in 1984.[citation needed] The drug was first proposed for scheduling by the DEA in July 1984,[5] and was classified as a Schedule I controlled substance in the United States from May 31, 1985.[9] In the late 1980s and early 1990s, ecstasy was widely used in the United Kingdom and other parts of Europe, becoming an integral element of rave culture and other psychedelic/dancefloor-influenced music scenes, such as Madchester and Acid House. Spreading along with rave culture, illegal MDMA use became increasingly widespread among young adults in universities and later in high schools. It rapidly became one of the four most widely used illegal drugs in the U.S., along with cocaine, heroin and cannabis.

Mechanism of action

MDMA's effects are due primarily to the drug's higher affinity for SERTs than serotonin itself. SERTs are the part of the serotonergic neuron which removes serotonin from the synapse to be recycled or stored for later use. Not only does MDMA inhibit the reuptake of serotonin, but it reverses the action of the transporter so that it begins pumping serotonin into the synapse from inside the cell.[10] This usually causes the serotonin storage vesicles to be emptied after only a few hours with a standard recreational dose. In addition, MDMA has a partial affinity for blocking the reuptake of dopamine and a smaller affinity still for blocking that of norepinephrine as well as other neurotransmitters in smaller quantities. The former two neurotransmitters, amongst others which may also be released in small amounts, are responsible for increased energy and contribute to the "speedy" feeling of the drug experience, whereas serotonin contributes primarily to feelings of well-being, euphoria, and decreased hostility. The empathic action of MDMA is still not well understood, but one theory is that oxytocin, a hormone and neurotransmitter crucial to social bonding, is released in large quantities when MDMA is taken.[11]

Neurological overview and toxicity

It has been established that MDMA affects the brains of humans and lower primates differently, especially in terms of long-term changes. In both animals, MDMA causes a reduction in the concentration of serotonin transporters (SERTs) in the brain. Baboons who were given a neurotoxic dose of MDMA only showed partial regrowth of SERTs when scanned a year later.[32] In contrast, human studies differ in that those who had never used ecstasy were indistinguishable in PET brain scan studies from former ecstasy users. However, the same study also concluded that the reduction in memory performance due to heavy, prolonged MDMA use may be long-lasting.[33]

Although oxidative stress (see neurotoxicity theory below) may cause SERTs to degrade faster than they are able to be replaced, the serotonin axon itself seems to have been spared, which indicates that neurotoxicity may not be the means by which SERT count was reduced. It is possible that excess serotonin in the synapse due to MDMA, especially if uses occur within a short period, causes the serotonin cells to produce fewer SERTs, a phenomenon which has already been demonstrated with other serotonin-depleting drugs.[34] MDMA use may also cause a decrease in the number of serotonin receptors on the dendrite of the neuron. (See down-regulation theory below.)

Neurotoxicity Under another theory, MDMA is considered neurotoxic in humans. While the method of this toxicity has not been definitively established, the current leading theory is that the metabolism of MDMA-induced dopamine release leads to the lipid peroxidation of serotonergic neurons. This occurs when MAO-B breaks up dopamine into free radicals capable of damaging cells, leading to a reduction in SERT count and possibly damage or destruction of the axon itself, thus interfering with the integrity of the brain's serotonin network.[37][38] Normally, the brain is able to protect itself from oxidative stress, but it is believed that the aforementioned damage can be attributed to MDMA's unique interaction with serotonin transporters. Not only does MDMA reverse the normal functioning of the transporter in which case serotonin is pumped out of the cell, but once the stored serotonin has been depleted, the transporter begins to take up dopamine which has been shown to be toxic to serotonin cells by itself. Once MAO oxidizes dopamine inside the serotonin cell, the damage is greatly magnified. Several studies have demonstrated that such damage in the brain is reversible after prolonged abstinence from the drug.[39][40] In severe cases, however, the possibility for recovery of cognitive functions may be much more limited.[41] Neurotoxicity of serotonergic neurons would occur in selective areas of the human brain as serotonin cells are highly concentrated in certain areas such as the neocortex and hippocampus. Although some studies have demonstrated this, the rate at which this damage occurs is disputed. U.S. government-funded studies [42] performed by George Ricaurte at Johns Hopkins University, which have demonstrated catastrophic brain damage occurring due to MDMA exposure, have been widely discredited by the scientific community.[43][44] The second study on the subject, which claimed that a single recreational dose of MDMA could cause Parkinson's Disease in later life, was actually retracted by Ricaurte himself after he discovered his lab had administered methamphetamine, a known neurotoxin, and not MDMA.[45] Antioxidants have been shown to prevent the neurotoxicity of MDMA in rats. In one study, intravenous administration of alpha lipoic acid completely blocked the neurotoxic effects of MDMA. No scientific experiment has been performed to date with human subjects, although some users report that taking various combinations of antioxidants before, during, and after using MDMA serves to moderate the subsequent mood-dip and improve recovery time.[46] The administration of an SSRI in rats prior to the administration of MDMA has been shown to completely block neurotoxicity. This is due to the binding of such medications with SERTs. However, administering an SSRI prior to administration of MDMA also completely or partially blocks the desired effects of the latter, something a large number

of users prescribed an SSRI have reported. As a compromise it has been shown that administration of an SSRI 3-4 hours after MDMA, at which time the primary effects will have tapered off significantly, markedly limits neurotoxicity overall despite some axonal damage having already occurred.[47] Once again, no such scientific experiment has been performed on human test subjects, and potential complications may still exist. It should also be noted that the production and introduction into the active brain of serotonin is a much lengthier process than is that of dopamine.(48). Therefore, users who redose once the serotonergically-induced effects of MDMA have mostly diminished are likely not stimulating the release of serotonin at all as a single recreational dose of MDMA is likely to have depleted these rather limited reserves. The subsequent effects of redosing are therefore due almost entirely to the action of increased dopamine in the brain, and therefore, once again, neurotoxicity is significantly enhanced. Psychological MDMA use commonly results in a rebound period of poor mood or possibly depression commonly known as a "comedown", the length and severity of which depends on the user, the dose and the total duration of MDMA's activity in the body. Heavy or frequent use may precipitate lasting depression and anxiety in vulnerable users, particularly those prone to depression or other mental disorders as well as anyone in a state of crisis in their life. Based on the fact the MDMA causes the release and metabolization of serotonin, it's not uncommon to see users try to compensate for the possible receptor down-regulation and/or prevent serotonin levels from becoming depleted. 5-Hydroxy-Tryptophan (5-HTP) is an immediate precursor to serotonin, and taking 5-HTP supplements during the come down and the days following can significantly minimize the intensity of the come down and depression that may follow, although supplements can only do so much. In cases where the onset of depression is not soley attributed to biological factors, taking supplements to elevate mood may not be successful. If too much 5-HTP is taken prior to taking MDMA then it's possible for the brain to produce too much serotonin on accident, inducing the potentially fatal Serotonin Syndrome. "Redosing" in an attempt to extend MDMA's desired effects has been shown to substantially increase neurotoxicity as well as the undesired physical side effects associated with MDMA use such as trisma and bruxia, which are caused by MDMA's partial dopaminergic affinity. The longer MDMA is active and being metabolized in the brain, the greater the neurotoxic damage and the greater the risk of short-term emotional problems. The more occasions MDMA is used, the greater the chances of long-term problems.[49] Deficits of memory have been shown in long term MDMA users.[50] This may be odue to long-term depletion of serotonin, one of the neurotransmitters involved in memory function. However, this is not conclusive proof of neurotoxicity and may be the result of neural plasticity.[51]

Research using MDMA in PTSD, alcoholism addiction and despression

The Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) is funding pilot studies and clinical trials investigating the use of MDMA in psychotherapy to treat posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD),[52] social anxiety in autistic adults,[53] [54] and anxiety in terminal illness.[55]. In November 2016, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved large-scale phase 3 clinical trials involving the use of MDMA for the treatment of PTSD in individuals who do not respond to traditional prescription drugs or psychotherapy.[56] In 2017, doctors in the UK began the first clinical study of MDMA in alcohol addiction.[57]. A 2014 review of the safety and efficacy of MDMA as a treatment for various disorders, particularly PTSD, indicated that MDMA has therapeutic efficacy in some patients;[58] however, it emphasized that issues regarding the control-ability of MDMA-induced experiences and neurochemical recovery must be addressed.[58] The author noted that oxytocin and D-cycloserine are potentially safer co-drugs in PTSD treatment, albeit with limited evidence of efficacy.[58] This review and a second corroborating review by a different author both concluded that, because of MDMA's demonstrated potential to cause lasting harm in humans (e.g., serotonergic neurotoxicity and persistent memory impairment), "considerably more research must be performed" on its efficacy in PTSD treatment to determine if the potential treatment benefits outweigh its potential to harm to a patient.[58][59]

References

- Stimulants, narcotics, hallucinogens - Drugs, Pregnancy, and Lactation, Gerald G. Briggs, OB/GYN News, June 1, 2003.

- Ask Erowid. Erowid.

- Roland W. Freudenmann, Florian Axler, Sabine Bernschneider-Reif (2006). The origin of MDMA (ecstasy) revisited: the true story reconstructed from the original documents. Addiction 101, 1241-1245. PMID 16911722 PDF

- Benzenhafer, U. and Passie, T. (2006). The early history of "Ecstasy." Nervenarzt 77, 95–99. (Article in German) PMID PDF

- Pharmaceutical company unravels drug's chequered past (HTML) (2005).

- Saunders, Nicholas. Ecstasy Reconsidered (1997), page 7.

- Tom Shroder, "The Peace Drug", Washington Post Magazine, November 25, 2007

- The Austin Chronicle - "Countdown to Ecstasy" by Marc Savlov

- Erowid MDMA Vault : Info #3 on scheduling

- MDMA Makes the Serotonin Transporters Work In Reverse, at dancesafe.org

- A role for oxytocin and 5-HT(1A) receptors in the prosocial effects of 3,4 methylenedioxymethamphetamine ("ecstasy")

- Erowid MDMA Vault : Effects

- Heffter Research Institute

- Saunders, Nicholas. Ecstatsy and the Dance Culture (1995), page 168

- Saunders, Nicholas. Ecstasy Reconsidered (1997), page 237

- [http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/rds/pdfs/hors227.pdf Home Office Research Study 227 Middle market drug distribution], page 22

- http://www.london.gov.uk/mayor/health/drugs_and_alcohol/docs/highs-lows2.rtf

- "Is ecstasy MDMA? A Review of the proportion of ecstasy tablets containing MDMA, their dosage levels, and the changing perceptions of purity", AC Parrott, Psychopharmacology, March 2004: "The latest reports suggest that non-MDMA tablets are now infrequent, with purity levels between 90% and 100%."

- Heffter Research Institute

- Heffter Research Institute

- MAPS's MDMA Research Information "MAPS's MDMA Research Information".

- ] Beaumont, Adam. "Ecstasy" used to treat Swiss trauma victims". swissinfo.

- Nichols, David. "Erowid Character Vaults". erowid.org.

- "The Great Entactogen - Empathogen Debate". Newsletter of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, 1993.

- [1] Nov 05 DEA Micrgram newsletter

- MAPS. Documents from the DEA Scheduling Hearing of MDMA,.

- E for Ecstasy by Nicholas Saunders, Appendix 1: Reference Section

- Science and Technology Committee Report (page 176), 2006)

- Nutt, D. and King, LA and Saulsbury, W. and Blakemore, C. (2007). Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. 1047--53.

- Uncoupling the agony from ecstasy by Mills et. al. in Nature (2003), 426: 403-404.

- Glenn Gandelman, MD, MPH, Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine, New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY. (2007-2-14). Drug-induced hypertension. MedicinePlus Medical Encyclopedia. United States' National Library of Medicine.

- Scheffel U, Szabo Z, Mathews WB, Finley PA, Dannals RF, Ravert HT, Szabo K, Yuan J, Ricaurte GA. In vivo detection of short- and long-term MDMA neurotoxicity--a positron emission tomography study in the living baboon brain. Synapse. 1998;29(2):183-92. Abstract

- Reneman L, Lavalaye J, Schmand B, de Wolff FA, van den Brink W, den Heeten GJ, Booij J. Cortical Serotonin Transporter Density and Verbal Memory in Individuals Who Stopped Using 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy'): Preliminary Findings. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58(10):901-906. Abstract

- "p-Chlorophenylalanine Changes Serotonin Transporter mRNA Levels and Expression of the Gene Product", Journal of Neurochemistry, 1996. Online copy (pdf)

- Neurotoxicity, at TheDEA.org

- Down-regulation of Receptors: The most probable cause of ecstasy-related depression at DanceSafe.org

- Neurotoxicity at Dancesafe.org

- Does MDMA Cause Brain Damage?, Matthew Baggott, and John Mendelson

- Research on Ecstasy Is Clouded by Errors, Donald G. McNeil Jr., New York Times, December 2, 2003.

- Cortical Serotonin Transporter Density and Verbal Memory in Individuals Who Stopped Using 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or 'Ecstasy'): Preliminary Findings, Reneman L, Lavalaye J, Schmand B, de Wolff FA, van den Brink W, den Heeten GJ, Booij J. Archives of General Psychiatry 2001;58(10):901-906.

- The strange case of the man who took 40,000 ecstasy pills in nine years, David McCandless, The Guardian, April 4, 2006]

- Fischer, C. and Hatzidimitriou, G. and Wlos, J. and Katz, J. and Ricaurte, G. (1995). Reorganization of ascending 5-HT axon projections in animals previously exposed to the recreational drug (+/-) 3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA," ecstasy"). Soc Neuroscience.

- [http://www.erowid.org/chemicals/mdma/mdma_neurotoxicity3.shtml MDMA Brain Scans Showing Neurotoxicity Discredited Several Articles Highlight Questionable Science], Erowid, April 2002.

- Parkinson's at TheDEA.org

- Ecstasy Study Botched, Retracted, Kristen Philipkoski, Wired.com, 09.05.03

- Do Antioxidants Protect Against MDMA Hangover, Tolerance, and Neurotoxicity?, Earth Erowid, Dec 2001.

- The Prozac Misunderstanding at TheDEA.org

- Producing New Serotonin at DanceSafe.org

- Depression at DanceSafe.org

- Wareing, M. and Fisk, J.E. and Murphy, P.N. (2000). Working memory deficits in current and previous users of MDMA 181--8.

- XXXXX

- Zarembo A (15 March 2014). "Exploring therapeutic effects of MDMA on post-traumatic stress". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times.

- Danforth AL, Struble CM, Yazar-Klosinski B, Grob CS (January 2016). "MDMA-assisted therapy: A new treatment model for social anxiety in autistic adults". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 64: 237–49. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.03.011

- Maxmen A. "Psychedelic Compound in Ecstasy Moves Closer to Approval to Treat PTSD". Scientific American. Retrieved 18 May 2017

- Lattin D (19 March 2015). "Patients in ecstasy clinical trial find drug beneficial". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on 24 April 2016.

- Philipps D (29 November 2016). "F.D.A. Agrees to New Trials for Ecstasy as Relief for PTSD Patients". The New York Times Company. The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2016.

- Devlin H (30 June 2017). "World's first trials of MDMA to treat alcohol addiction set to begin". The Guardian.

- Parrott AC (2014). "The potential dangers of using MDMA for psychotherapy". Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 46 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1080/02791072.2014.873690. PMID 24830184.

- Meyer JS (2013). "3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA): current perspectives". Substance Abuse and Rehabilitation. 4: 83–99. doi:10.2147/SAR.S37258. PMC 3931692. PMID 24648791.

Molecules of Life Resources

The Cannabidiol Molecule

Cannabidiol (CBD is the major non-psychoactive component of Cannabis and is being looked at by major drug and consumer companies for various medical and social uses.